Originally Published by...

When Hackney was a just Farming Village: Everyday Life (and Death) in the Sixteenth Century

Today, a stroll down Stamford Hill would likely see you passed by the 253 or 254 busses, along with a parade of Hackney’s other traffic trickling down the A10. This ancient road dates back nearly two millennia to the Roman era, when it stretched over the rolling fields that would later become Hackney, connecting the forum of Londinium and the city of York. It remained as one of the key entrances to London and over the centuries countless people have travelled its route, passing through to work, trade, or visit the capital.

During the Tudor period (1485-1603) the road gained even greater prominence as increasing quantities of goods flowed from the countryside to the city, fuelling the expanding silk and textile industry. In 1550 the city had a population of around 120,000, of which 1/3 of the adult male population were employed as spinners, weavers, fullers, delivery drivers, brushers, shearers, dryers or packers in this industry. Most of these workers were gathered in the eastern corner of London’s city walls near to modern-day Aldgate. Even five centuries ago, the area was a melting pot of diverse cultures – of course not to the same global extent we witness today. It has been estimated that at the time roughly 4-5% of the population were immigrants, mostly from France, Ireland and the Netherlands, with a handful of African families also residing in the capital’s east end.

Just north of the bustling textile trade beyond the city walls was the idyllic landscape of sixteenth century Hackney. Its rolling hills and farmland stretched all the way to the River Lea – slightly different to the place many call home today! Most of the area was owned by the church which had prevented excessive building developments and limited the sprawl of London beyond its eastern wall. It was frequently used for grazing livestock and growing crops with many travelling from outside the city to do so. The Shoreditch area was slightly more built-up than most places outside London’s walls with small single-story cottages surrounded by modest smallholdings and manorial homes dotted across the landscape. One example of these manor houses just north of this area that can still be visited is Sutton House. The streets connecting Shoreditch to Whitechapel were paved with stone and eventually led to the A10 road – at this point known as Bishopsgate Street. There are relatively sparse references to these areas of Hackney in the historic records apart from Hoxton Fields. They were known as a favoured spot for Henry VIII's Honourable Artillery Company who regularly practiced archery in the fields and there were several crown mandates that water collected for the city of London should only be taken from this area. It is unclear exactly why this may have been, but one reason was probably the cleaner air and water that Hackney would have had compared to inside the capital’s walls.

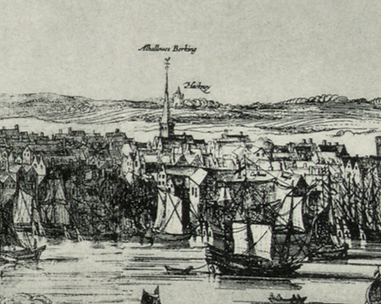

The 1616 Visscher Panorama of London where Hackney can be seen outside the city walls as a small village.

The records of individuals who lived in Hackney or those who travelled through it as part of the east London textile trade is sparse. Any granular information about their lives can usually only be found in incidental references in varying sources. One glimpse into this past is a coroner’s report from the mid-sixteenth century. It stated that on Monday the 9th of May 1555 a man called Anthony Kynges, from a village called Naffying in Essex, was riding down the A10 road delivering a cartful of coal and wool to London. Kynges, still obviously exhausted from his previous weekend’s festivities, struggled to stay awake at the reigns and ended up falling asleep. Unfortunately for him this lapse in consciousness proved fatal. Upon reaching the uneven, sloping road at the top of Stamford Hill he was thrown from the cart and landed underneath its wheels killing him instantly.

An inquest always followed any accident during this period. This was because if foul play could be proven the king had the right to seize all possessions of the victim and perpetrator. Unlike Hackney’s modern systems, sixteenth century inquests were cumbersome and deeply inefficient – well slightly more efficient. The Shoreditch coroner William Dawson was responsible for inspecting accident scene but he only turned up to the scene seven days after the incident – meaning the delivery man’s body had languished at the side of the road for a week before it could be moved. Dawson concluded that Anthony Kynges had “accidentally fallen out of the cart and one of the wheels had crushed his forehead.” Because Dawson had ruled that he had died accidentally, Kynges possessions were returned to his next of kin and the crown could not take control any of his land.

Another story seven years after Kynges and Dawson’s is from Thursday 16th of August 1562. The assistant yeoman farmer John Toyes of Hackney was riding the horse of his master William Marleton of Shoreditch through the River Lea. As Toyes came to cross the river he lifted his legs from the saddle and placed them on the neck of the horse to avoid getting them wet. In doing so he startled the horse and fell off it backwards into the River Lea. The strong current pulled Toyes out of his depth, and given the lack of swimming lessons most Tudor Hackney citizens had, Toyes unfortunately drowned in the river. As with Kynges’ the new Shoreditch coroner Thomas Went was slightly late turning up a couple of days after the incident. Went summarised that Toyes must have accidentally perished and therefore the horse was returned to Marleton’s Hackney farm.

Though these two grim stories are undeniably morbid, they offer a rare glimpse into the lives of ordinary people from Hackney’s deep past. They humanise those whose existence has largely been erased by time. They give us a chance to imagine how the everyday residents of Hackney might have lived, whether that be riding coal carts into the City of London or riding horses across the River Lea. While we only have records of the unfortunate and untimely deaths of Anthony Kynges and John Toyes, their experiences allow us to piece together a picture of how they may have spent their days before tragedy struck.

These are the forgotten stories of Hackney, slowly fading as local evidence is lost to time. It is ironic that such lives are preserved in history only through records of their death, yet these are the ways in which ordinary people, not kings or queens, are remembered. Their stories offer a fleeting window into a previous era, helping us understand how life in Hackney might have unfolded before the Industrial Revolution, before the British Empire, and before London’s great expansion into the farming village of Hackney.