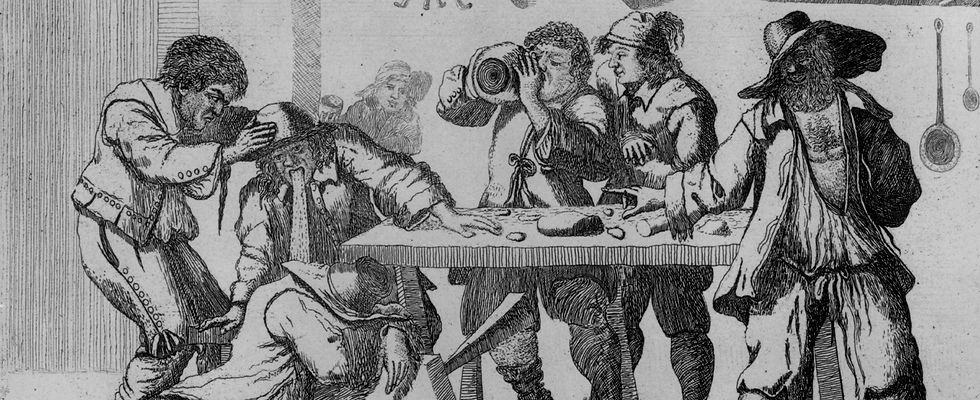

Making Merry of Destructive Drinking: Uncovering Peasant Drunkenness in England, 1552-1606

In 2020 the entire hospitality sector in the UK was forced to close its doors early to prevent excessive drinking on their premises. The suggestion was that a late closure might lead to patrons failing to adhere to COVID-19 restrictions. While there was general uproar about this legislation, its implementation was just the latest addition of a long line of laws seeking to protect those who were consuming vast amounts of alcohol that stretches back throughout both modern and early modern English history.

Unfortunately, most of these mothering laws were brought into effect years too late to protect some like James Johnson. Nothing is known whatsoever about Johnson except for one surviving record: his coroners report. Carried out by a man called Thomas Agar on the 22 August 1565 at around 1pm it offers us a tiny window into the everyday life of peasants in sixteenth century England. In early modern England corner’s reports were generally carried out a day or a few days after an incident where foul play or an accidental death was thought to have occurred. It was there job to inspect the body and the surrounding area, discuss with people in the local community and then collate a small report of the findings to submit to the crown.

So what did Agar find out? Supposedly late in the evening of the 21 August 1565, Johnson drunkenly stumbled out of a tavern in the London Bourgh of Southwark at about 8pm looking to walk back to his home. This was the last time anyone would see Johnson alive. Floundering along a lane towards the Clink, a prison on the southern side of the River Thames, Johnson was soon overcome by his alcoholic indulgence. He decided to sleep near a ditch on the side of the lane after the debilitating effects of his drinking had overwhelmed him. And when he awoke “barely possessed of a healthy and calm mind from his great drunkenness” he decided to “empty his bowels, so he undid and let down his breeches” to his ankles. But as Johnson did, he lost his footing “and by misfortune fell face-first into the ditch, it being full of water, mud and filth.” Johnson was unable to stand because of his intoxicated state and the breeches which were tangled around his legs. He drowned in the filth of the ditch on the 21st August 1565 at 8pm. It was not until the next morning he was discovered.

The gruesome description of Johnson’s demise offers us more than a droll tale of accidental death or an example of great misfortune as a result of excess drinking. It provides a window, from which quotidian life can be viewed. These snapshots offer us the ability to understand what people were doing on a day-to-day basis in the potentially ‘lost past’. If you take a step back from the death itself you can understand patterns of life. For example in Johnson’s case we can understand that it was totally normal and expected for a person to be so inebriated at 8pm they drown in a puddle. We can also begin to understand the times at which people would head home and therefore begin to understand what time people may have gone to bed.

There are hundreds of death records that list excessive drinking as the reason for a person’s untimely end. By collecting as many of these as possible then one can begin to piece together the jigsaw of early modern life. This is not the history of Henrician religious reform or the Spanish Armada. This is history from below. A history which seeks to elucidate everyone’s past, not just royalty. Regrettably, death records are one of the few ways by which this past can be reconstructed.

For the full essay please click below.

Uncovering Peasant Drunkenness in England, 1552-1606.